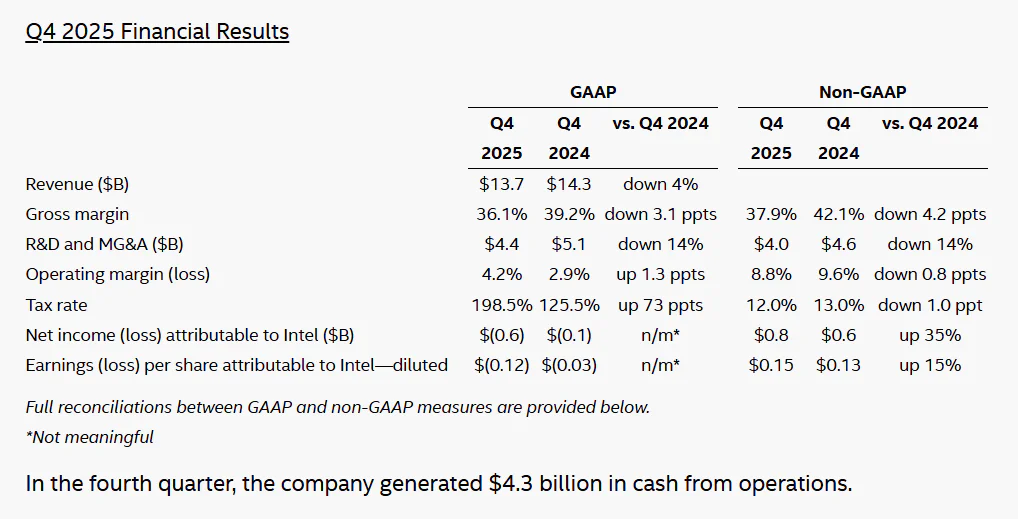

Intel’s latest earnings report points to a company under pressure from tight manufacturing capacity, prompting tough trade-offs that are influencing its product strategy. The chipmaker posted fourth-quarter revenue of $13.7 billion, down 4% year over year but still near the top of its forecast range. Annual revenue edged down slightly, slipping from $53.1 billion to $52.9 billion.

The numbers point to a clear problem for Intel. It’s selling almost everything it produces, but supply shortages mean it still can’t keep up with overall demand. That gap is pushing the company to focus on higher-margin data center and AI chips, while tightening supply for the consumer PC market.

Data Center and AI revenue climbed 9% in the quarter and 5% for the year, helped by cloud companies and enterprises rolling out new Xeon chips and AI accelerators. On the other hand, the Client Computing Group, which handles Core CPUs and Arc GPUs, saw revenue slide 7% in the quarter and 3% over the full year.

As a result, Intel is reallocating its internal manufacturing resources toward the higher-margin data center segment. Chief Financial Officer David Zinsner said the company is concentrating its in-house wafer supply on data center products, while outsourcing a larger share of consumer chip production to foundries such as TSMC.

That focus could have knock-on effects for Intel’s next consumer chips. Products like the Core Ultra Series 3, codenamed Panther Lake, may face supply constraints or higher prices. Unlike some recent designs, these processors are set to be made largely in-house, which makes them more sensitive to Intel’s manufacturing bottlenecks.

Zinsner acknowledged that Intel cannot step away from the client market, but said the company is shifting as much manufacturing capacity as possible toward data center products. The move mirrors where demand and profitability are strongest, particularly as available wafer supply remains fully allocated.

Much of Intel’s production trouble traces back to its new 18A process, which is central to the company’s comeback plan. The transition hasn’t been smooth, with early yields starting off painfully low. By mid-2025, reports indicated that only about 10% of early wafers were usable. Intel says things are getting better, yields are improving by 7% to 8% each month, but they’re still not where the company wants them.

CEO Lip-Bu Tan said current 18A yields are “in line with internal plans,” while conceding they have yet to reach optimal levels. Tan and CFO David Zinsner both suggested production should begin to rebound in the second quarter of 2026, with the first quarter marking the low point of the current supply squeeze.

Looking forward, Intel is pressing ahead with its fabrication roadmap. The company continues to refine its 18A process while developing its next-generation 14A node. Together, these technologies are meant to position Intel’s foundries to produce chips for outside customers for the first time in decades, with initial partner commitments expected between late 2026 and early 2027.

On the design side, Intel plans to release its next-generation Nova Lake architecture at the end of 2026. This platform will unify desktop and laptop processors and will utilize the 18A process for at least part of its production.

Despite near-term supply pressures, Intel showed solid resilience in the fourth quarter, driven by steady demand for AI and data center solutions. Going forward, the company must balance increasing production to meet accumulated consumer demand with executing its next-generation node and architecture plans, a challenge that will shape its direction through 2026 and beyond.

Maybe you would like other interesting articles?