When engineers discuss soft robots, precision is often the weak link. Building flexible machines has never been the hard part; getting them to move in controlled, repeatable ways has. Researchers at Harvard University now claim they’ve cracked that problem using a 3D-printing method that programs motion directly into the material.

Detailed in the journal Advanced Materials, the technique moves away from the slow, multi-step molding and casting processes that have long dominated soft robotics. Instead, the researchers demonstrate a 3D-printing approach that produces structures designed to twist, curl, or bend in precise ways when air is pumped through embedded channels.

The research was conducted in the lab of Jennifer Lewis, a leading figure in multimaterial 3D printing. Graduate student Jackson Wilt and former postdoctoral researcher Natalie Larson combined several of the group’s existing techniques into a system they call rotational multimaterial 3D printing, which enables multiple materials to be deposited through a single rotating nozzle.

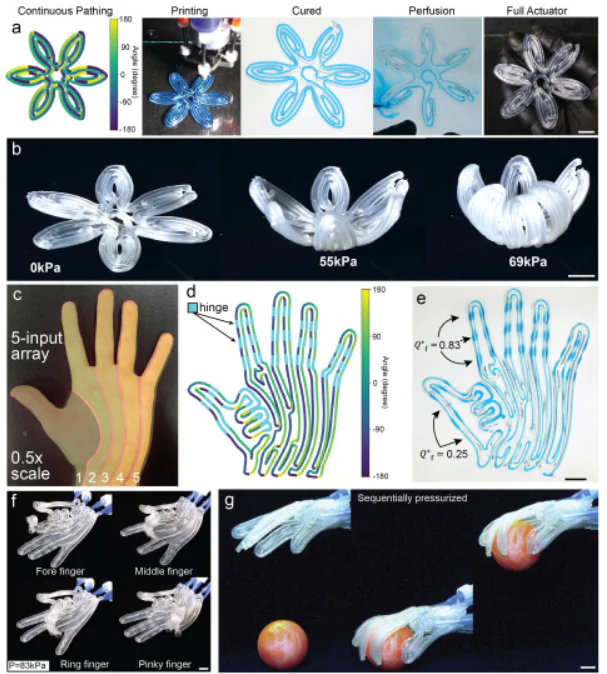

By rotating the nozzle continuously during printing, the researchers can precisely control how each material is positioned within the filament, much like tracing a helix inside a tube. A tough polyurethane forms the outer shell, while a gel-like polymer known as a poloxamer, commonly found in hair care products, fills the interior where pneumatic channels will eventually form. After the print solidifies, the inner gel is removed, leaving carefully shaped hollow passages.

The hollow channels function like programmable muscles. When air or fluid is pumped through them, the structure bends, twists, or stretches in controlled, predetermined ways. By varying the internal orientation of each filament, the researchers effectively encode motion directly into the material.

“We use two materials from a single outlet, which can be rotated to program the direction the robot bends when inflated,” Wilt said.

The approach simplifies soft robot design by consolidating fabrication into a single printing step. Rather than assembling multiple cast and sealed components, the printer produces a complete actuator at once. Because the hardware remains unchanged, designers only need to modify printing parameters. As a result, devices that previously required days to assemble can now be redesigned within hours.

To showcase the technique, the researchers produced two demonstration pieces: a spiral actuator that opens like a flower when inflated, and a gripper with articulated fingers that curl around an object. Both devices were fabricated as continuous 3D-printed structures.

The approach has applications outside traditional industrial robotics. Programmable soft materials could be used in adaptive surgical instruments, body-conforming wearable assistive systems, and end-effectors designed to manipulate fragile components during manufacturing.

Natalie Larson, now a faculty member at Stanford University, describes the work as a conceptual shift for soft robotics. Instead of adding motion as a separate step, she and Wilt argue that function can be printed directly into the structure from the outset. In this approach, geometry becomes a form of code, giving designers precise control over how a soft system behaves once activated.

Maybe you would like other interesting articles?