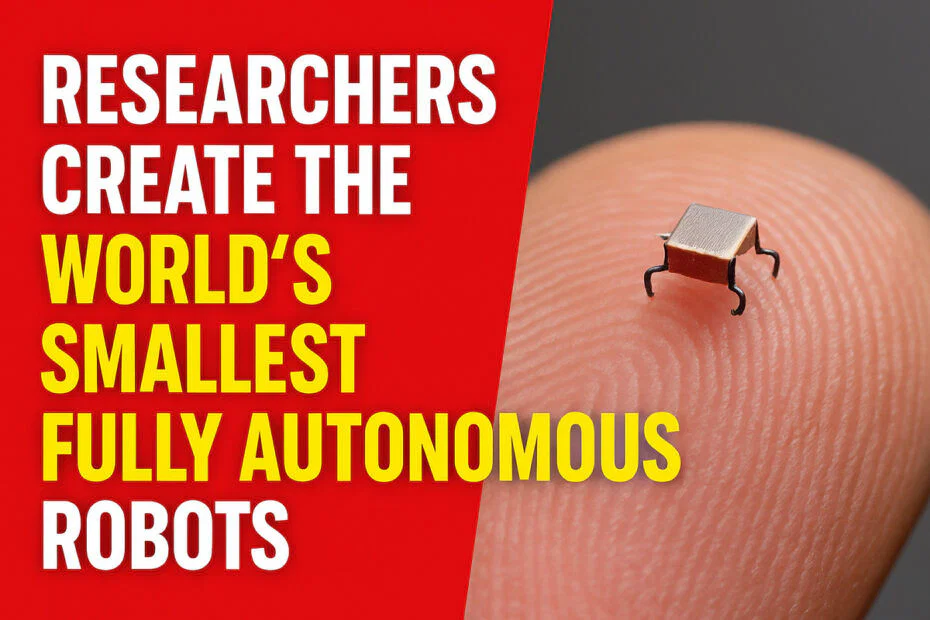

A research team from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan has developed the world’s smallest fully programmable autonomous robots. Each one is smaller than a grain of salt, costs roughly one cent, and runs independently without wires, magnetic fields, or external controllers, pointing to new possibilities across medicine, manufacturing, and biology.

As reported in Science Robotics and PNAS, the work shows just how small autonomous robots can now be. Measuring roughly 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers, each device is tiny enough to operate in the same space as individual cells.

“That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots,” said Marc Miskin, Assistant Professor of Electrical and Systems Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, who led the project. In an interview with Science Alert, he noted these robots are 10,000 times smaller than current state-of-the-art microbots.

At such a tiny scale, the laws of physics change. Inertia and gravity become negligible, while surface forces like drag and viscosity dominate. “If you’re small enough, pushing on water is like pushing through tar,” Miskin explained.

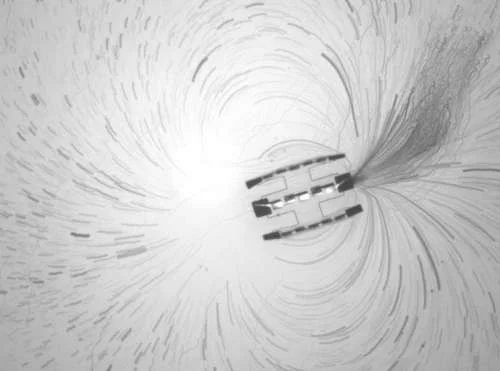

Because traditional mechanical parts fail at this scale, the researchers developed a propulsion method with no moving components. The robots generate electric fields that influence ions in the surrounding fluid, causing water molecules to move and creating a current that drives the robot forward.

“It’s as if the robot is in a moving river,” Miskin said, “but the robot is also causing the river to move.” This approach allows the robots to travel about one body length per second, navigate complex paths, and even coordinate movements like a school of fish.

Movement alone isn’t enough to qualify as autonomy. To add decision-making capabilities, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania partnered with a team from the University of Michigan, which is known for developing the world’s smallest computer.

The circuits, designed by David Blaauw’s group, are optimized for ultra-low-voltage operation, driving power consumption down by more than three orders of magnitude. Power comes from microscopic solar cells that deliver only 75 nanowatts, over 100,000 times less than the energy budget of a smartwatch.

Even with tight limits on space and power, the robots pack in a processor, memory, temperature sensors, and motor controls. They can sense temperature changes down to about a third of a degree Celsius and respond on their own, like moving along heat gradients linked to biological activity.

Because radio antennae can’t be scaled down far enough, communication became a major challenge. The researchers addressed it by encoding data into small, coordinated movements that are observed under a microscope.

“We designed a special computer instruction that encodes a value, such as the measured temperature, in the wiggles of a little dance the robot performs,” Blaauw explained. “It’s very similar to how honey bees communicate with each other.”

Individual robots can be programmed and powered via targeted light pulses, enabling task differentiation within large swarms. The minimalist solid-state architecture contributes to high durability, allowing repeated transfer between samples and sustained operation over periods of months.

The researchers see this as a starting point, not a finished product. They point to a wide range of possibilities, from tracking cellular health and helping with microscopic manufacturing to moving through tissue for medical diagnostics or working as tiny sensor networks in confined spaces.

Maybe you would like other interesting articles?